The post How Much Can You Save by Switching to LED Lighting? appeared first on Carbon Switch.

]]>But for now, let’s chat dollars and cents and answer one question: how much can you save with LEDs?

How to calculate the energy and cost savings of LED lights

The average home with incandescent bulbs uses about 2,000 kWh of electricity per year.

At the national average of $0.10 per kWh, these homeowners spend $215 a year on lighting. By switching to LEDs, you can save around $4,000 over 20 years (the typical lifespan of an LED). As far as energy efficiency projects go, that’s a lot!

To put that in perspective, consider that switching to a heat pump water heater (another great savings opportunity) will save you about $200 per year and $5,000 over its 15-20 year lifespan. And switching to a heat pump (for heating and cooling), can save you as much as $1,000 per year and $15-20k over its lifespan.

If you want to calculate exactly how much you’ll save, you need to base it on everything from your location to how big your house is to what kinds of lights you’re currently using. Here, we’ll walk through some averages and calculations to help you get a more realistic number for your personal use case.

Energy use of light bulbs across the U.S.

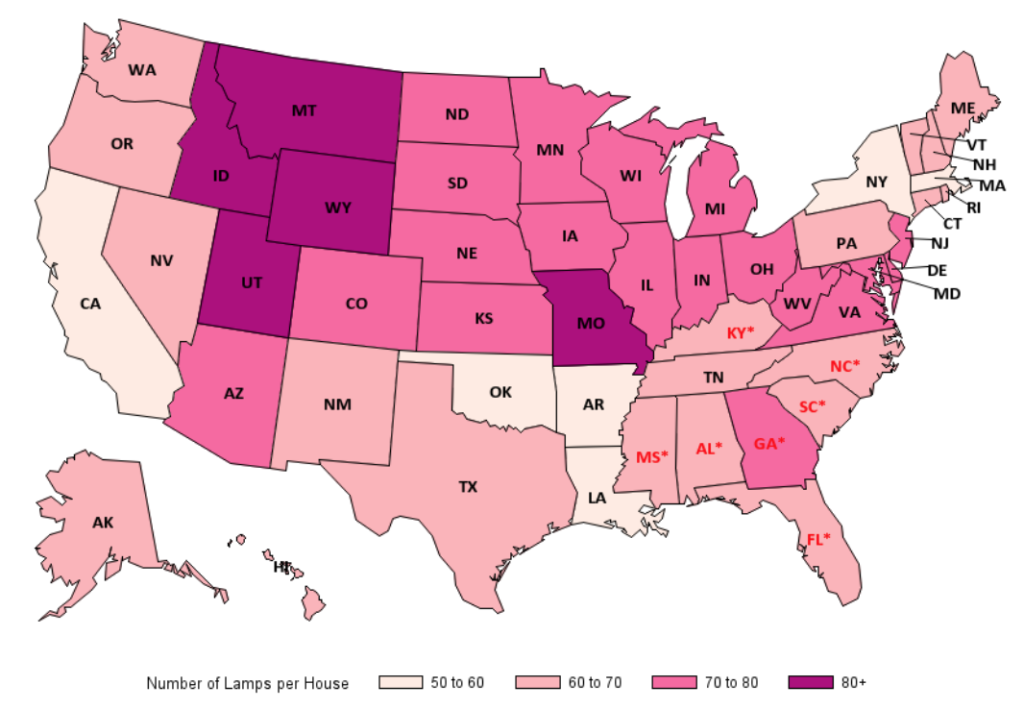

As you can see in the map below, the number of bulbs per house varies depending on where you live. Across the United States, the average number of light bulbs per house ranges from about 50 to 80, according to the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Of course, if your home is bigger than the national average—about 2,000 square feet—then you’ll likely have more bulbs. And vice versa.

And if you want an exact figure, you can count how many bulbs are in your house. But if you’re way over or under the average, it might be time for a lighting redesign to get you closer to what most people are using.

Energy use of light bulbs in each room of the house

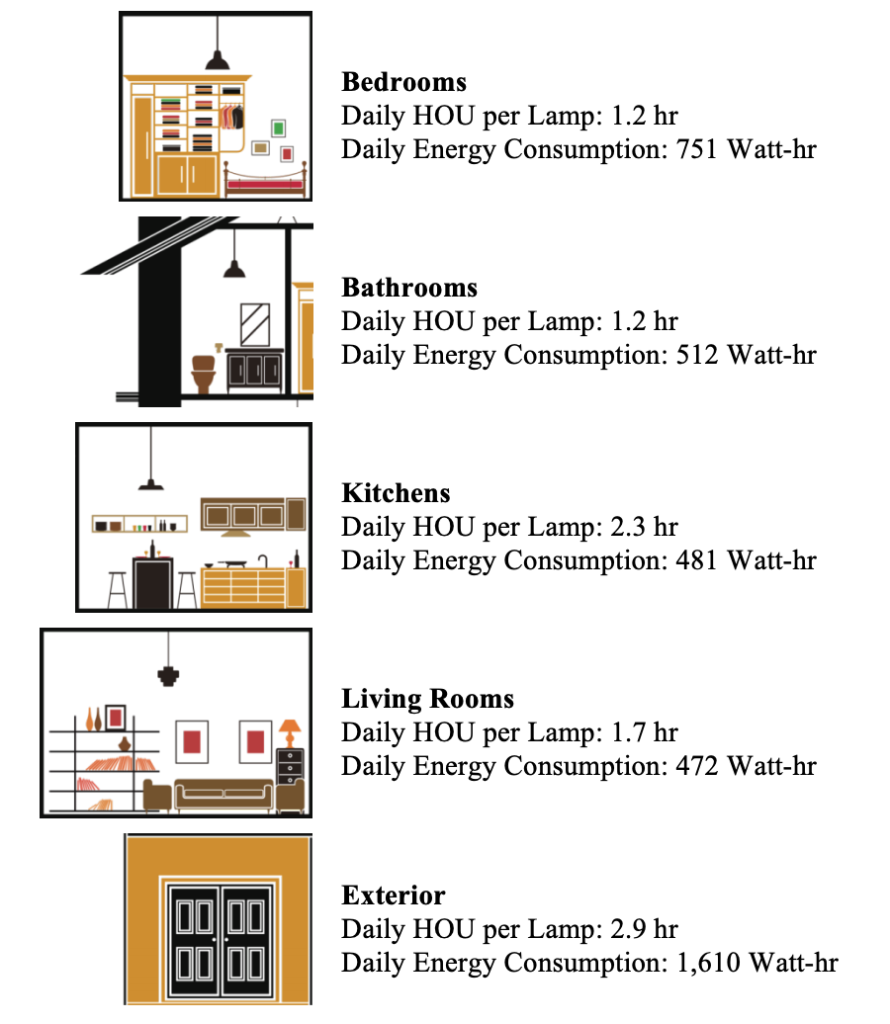

The next factor to consider is how much you use your lights. Here’s a chart with all the data you need to make a good estimate of that.

Note: in the image, HOU stands for hours of use.

As you can see, most homeowners use their lights between 1 and 3 hours per day on average.

How to calculate your potential savings

People talk about electricity in the home in terms of kilowatt hours (kWh); as in, the average home uses 10,000 kWh of electricity per year. But if you look at a light bulb package, you’ll notice it gives you the energy used in watts (e.g., a 60W bulb). So how do you turn watts into kilowatt hours?

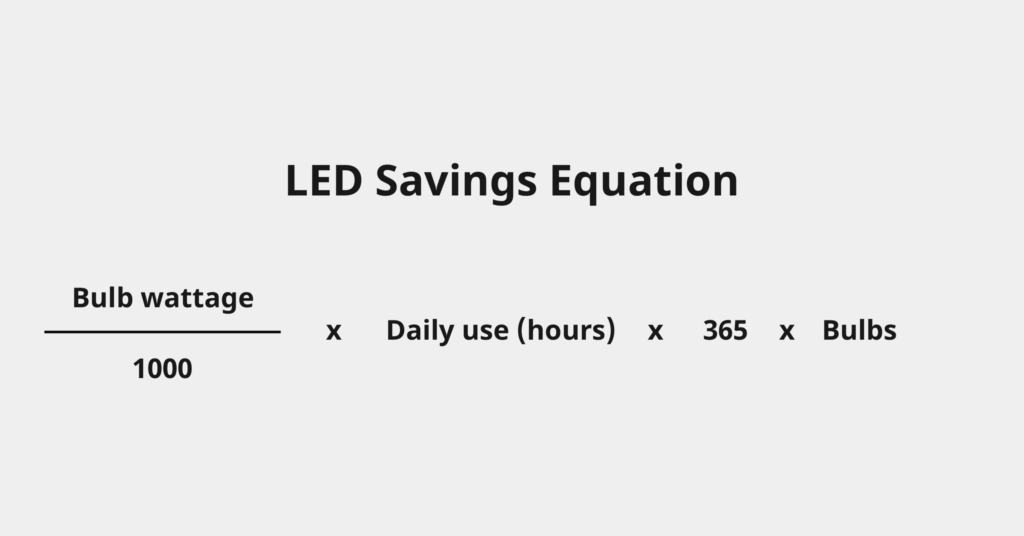

You can use the following equation to calculate the energy used by lighting in your home:

If you’re like me, math might not be your forte. So let’s go over an example to show how that equation works:

- That 60W on the package means that your light bulb uses 60 watts of energy every hour that it’s on. That’s equivalent to .06 kWh (60W / 1000 = 0.06 kWh).

- That means that a 60W light bulb used for 2 hours per day uses 43,800 watts of electricity or 43.8 kWh every year (0.06 kWh * 2h * 365d = 43.8 kWh/year).

- So if you have 50 light bulbs that use that much energy in your home, that means you use 2,190 kWh of electricity every year on lighting (50 * 43.8 kWh = 2,190 kWh)

Once you have the total yearly electricity use, you can multiply that by your average yearly electricity rate to find how much it costs to light your home. At the national average electricity rate of $0.10, we’re looking at $219 per year spent on lighting ($0.10/kWh * 2,190 kWh = $219).

To get an even more precise estimate of your savings (which honestly, might be overkill), you’ll also want to think about lumens.

For a detailed understanding of watts vs. lumens, take a look at our guide to LED lights. But for our purposes here, just know that although watts and lumens measure different things, the general conversion is 60W incandescent bulb = 800lm LED bulb. So if we’re following the same example as above, here’s what it would look like.

- LEDs that create 800lm of light use 10W of energy, or 0.01 kWh (10W / 1000 = 0.01 kWh).

- A 10W LED bulb that is used 2 hours per day uses 7,300 watts or 7.3 kWh per year (0.01 kWh * 2h * 365d = 7.3 kWh/year).

- A home with 50 lights used for that amount on average would use 365 kWh per year (50 * 7.3 kWh = 365 kWh).

Meaning if you had the national average electricity rate of $0.10 per kWh, you would spend $36.50 per year on electricity for lighting. This gives you a savings of $178.50 from the existing lights—over $6,000 throughout the course of home ownership—just from just the electricity savings.

But that’s not the only savings LEDs can give you.

If you’re replacing compact fluorescent lights (CFL) and not incandescents, the math is different. A CFL bulb with a brightness of 800lm has an energy use of 14W and a lifespan of 8,000 hours. Using the process above (with the assumption that all of the light bulbs in the home are CFLs), the average yearly electricity cost of lighting would be $51.10. Take a look at our guide to LEDs for more information.

How bulb lifespans affect costs and savings

Existing light bulbs, called incandescents, last for 1,200 hours on average. That means that if you use your bulb for 2 hours a day, you’d have to replace your bulb every 1.64 years. On average, you’re looking at spending $30 a year just on the light bulbs themselves.

LED light bulbs have lifespans of more like 25,000 hours. If you use it for 2 hours a day, you would only have to replace the LED once every 34.25 years—so basically never.

Over the course of those 34.25 years, you’d have spent over $1,000 on incandescents.

Read more about LEDs and home energy efficiency improvement projects

- LED lighting buyer’s guide

- LED temperature and color guide

- How to save money and energy with a heat pump

- Everything you need to know before switching to a heat pump

- Heat pump water heater buyer’s guide

The post How Much Can You Save by Switching to LED Lighting? appeared first on Carbon Switch.

]]>The post LED Temperature and Color Buyer’s Guide appeared first on Carbon Switch.

]]>Light bulb colors: soft white vs. cool white vs. daylight

If you’ve ever walked into a living room that felt kind of like a dentist’s office or had to squint when looking in the mirror in the bathroom, it’s probably because the light bulbs were the wrong color.

The difference between a soft warm light and a harsh blue light is massive. And that’s why it’s so important to find the right LED color and temperature.

So how can you find the right bulb for your home?

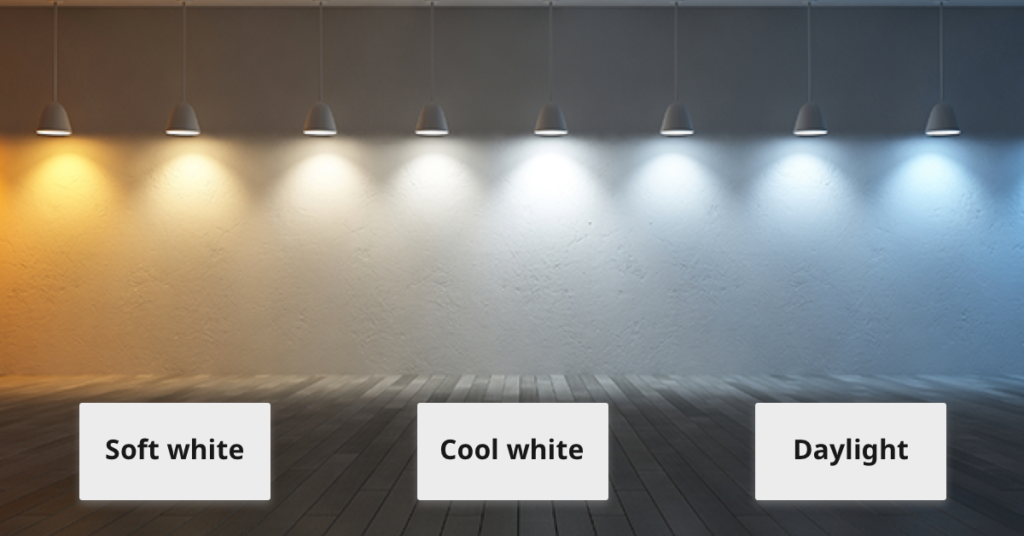

Light bulbs generally come in three “colors” (also called temperatures) with an associated amount of kelvins (we’ll get into that a bit later):

- Soft / warm white (2200K – 2700K) gives a warm and cozy (almost yellowish) hue to the room. It’s best for living rooms and bedrooms.

- Cool white (3000K – 4100K) is a more standard white color, and it’s most suitable for a kitchen, bathroom, or study room.

- Daylight (5000K – 6000K) gives off a bright, blueish light that works best for things like reading lamps. It’s usually not a good idea to use these for an entire room.

What does yellow, white, or blue mean in a light bulb?

We’re saying that bulbs give off a yellow, white, or blue hue. But obviously they don’t turn your room that color. Without getting too technical, here’s what’s happening: the hotter an object, the more types of visible light it gives off, appearing in whole at first as red, then white, and eventually bluish light.

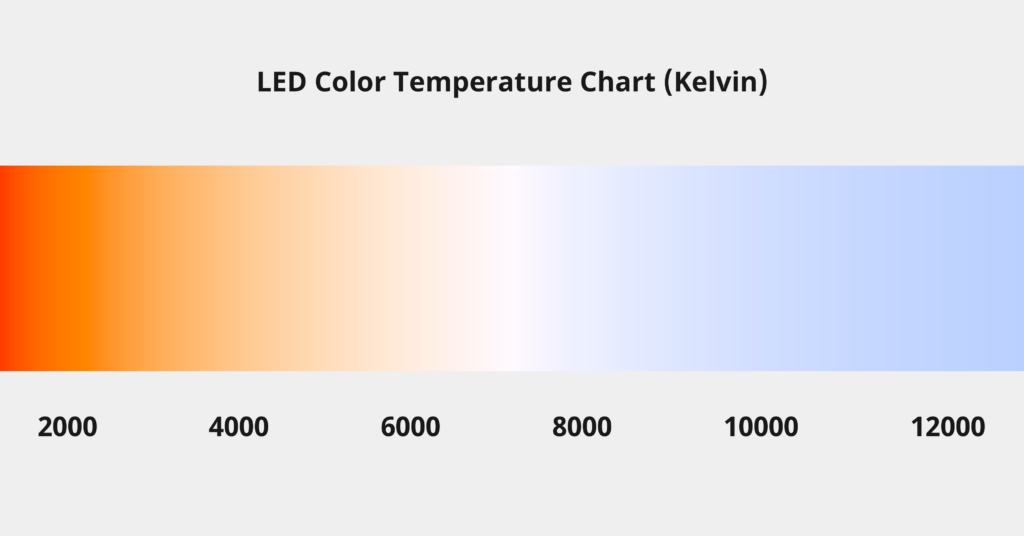

The following chart shows the progression of this color change, with the units at the bottom in kelvins. This range goes from oranger “warmer” light at 1,000K, which closely resembles candlelight, to bluer “cooler” light at 12,000K which resembles a clear blue sky.

The “cooler” the light (more kelvins), the closer to daylight the human brain thinks it is. This is what makes cooler bulbs perfect for areas where you need to be alert and be able to perceive contrasts, such as a kitchen, while these kinds of lights would make it harder to fall asleep if used in a bedroom.

Generally, you’ll want to use “warmer colors” (below 3,500K) for 70% of your lighting, saving the whiter or bluer lights in areas where more detailed work is done.

Light bulb color accuracy

The Color Rendering Index (CRI) is another thing you might see shouted out on a bulb label or description. Also known as color accuracy or high chromatic index (HCI), it measures how well the light shows colors.

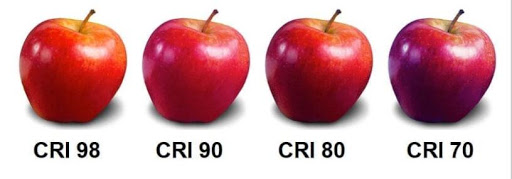

The image below, courtesy of Derun Lights, shows how different an object can look with different CRIs.

CRI is scored using a value from 0 to 100, where 100 is the score given to direct overhead sunlight. As you can see from the image above, objects under light bulbs with lower CRI scores appear washed out and can cause colors to blend or become dull. Objects under bulbs with higher CRI scores appear more crisp, and more variations of colors can be seen.

A CRI minimum of 80 is required to receive the Energy Star designation, but for areas where more detailed tasks occur, a CRI of 90+ is recommended.

The best light bulb lumens for each room

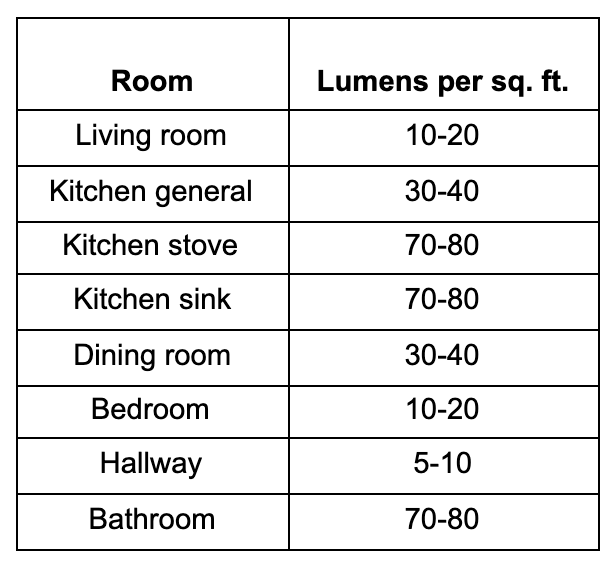

It’s not only about the color of your bulbs. You’ll also need a different amount of lumens (which measures brightness) depending on the room.

For more details on lumens, you can read our guide to LED lighting. But this chart gives you some general guidelines for how many lumens you’ll want in each room.

Generally, the more detailed work you expect to do in an area, the brighter you want the space to be and the higher lumen per square foot value you want. You can get the number of lumens you need from one bulb in one lamp, or you can spread it among many bulbs throughout the room.

Read more about LEDs and home energy efficiency improvement projects

- LED lighting buyer’s guide

- LED savings guide

- How to save money and energy with a heat pump

- Everything you need to know before switching to a heat pump

- Heat pump water heater buyer’s guide

The post LED Temperature and Color Buyer’s Guide appeared first on Carbon Switch.

]]>The post LED Lighting Buyer’s Guide appeared first on Carbon Switch.

]]>When you think about saving energy in your home you probably don’t think much about your light bulbs. How could a single bulb save much money?

That’s what I thought before I began this research. I knew I could save some energy by switching to LEDs, but I didn’t think it was worth the effort.

On top of that, I worried that LEDs were expensive and produced harsh light. I imagined my home looking more like a dentist’s office than a peaceful place where I could retreat to after a long day.

But I was wrong. To my surprise I learned three things:

- LEDs can save most homeowners thousands of dollars (see: LED savings)

- LEDs are cheap and pay for themselves in just a year

- LEDs come in all shapes, sizes, and colors (see our LED color and temperature guide)

But I wasn’t alone. American homeowners across the country waste billions of dollars every year on inefficient incandescent and CFL light bulbs.

And all that wasted energy leads to a lot of unnecessary pollution. Residential lighting emits 53 million tons of CO2 into the atmosphere each year. If we all switched to LEDs tomorrow we could cut that number by more than half.

In this article I’ll share everything I learned during my research into LED lighting and show you how to make the switch.

LEDs vs. CFLs vs. incandescent bulbs

There are three common types of light bulbs:

- Traditional incandescent

- CFL (compact fluorescent lights)

- LED (light emitting diodes)

In a traditional incandescent light bulb—the ones you’re probably looking to replace—light is created by heating a tungsten filament in the bulb. The filament is heated to the point where it starts to glow but does not meet its melting point (tungsten is used because it has the highest melting point of any metal). Although this process creates light, around 90% of the energy used is given off as heat and not light. Not great.

Halogen bulbs, and other “modern” versions of the incandescent bulb, operate using the same principle, often with modifications (such as filling the bulb with halogen gas) in order to increase operating life. But they still waste 90% of the energy on heat.

Compact fluorescent lights (CFLs) are easily recognizable because of their tubes of gas, which are often shaped in a swirl in order to maximize the light emitted by the vapor inside. They work by flowing electricity through argon and mercury vapor in a tube, creating ultraviolet light, which then interacts with a coating on the tube to create light. This process means that very little heat is created—but the process is also more energy intensive than a LED for the amount of light created, and it creates potentially dangerous ultraviolet light as a byproduct. Additionally, there’s the possibility of mercury being released into the local environment if the bulb is ever broken.

A decade ago, this was the light bulb you got to replace the traditional incandescent. It’s much more efficient than the incandescent, and because it’s been in development since the 1970s, it was in a position to scale up production in order to bring costs down enough to compete with incandescents. But the CFL technology has not been able to keep up with the advances in LEDs. CFLs generally fall between incandescents and LEDs in terms of price and energy use.

Light emitting diodes (LEDs) create light using circuits. Electricity flows into the bulb, where some interesting physics and semiconductor design work together to create light. Very little heat is produced during this process (as much as just having your phone or computer screen on), with up to 80% of the energy used resulting in visible light.

Because of this design, LEDs also last much longer. They have no moving parts, no parts undergoing thermal stress, and no gases and coatings which could wear off. This gives the LED bulb fewer points of failure, and allows it to continue operating long after other forms of lighting would have broken.

Converting lumens to watts: what to know when buying a light bulb

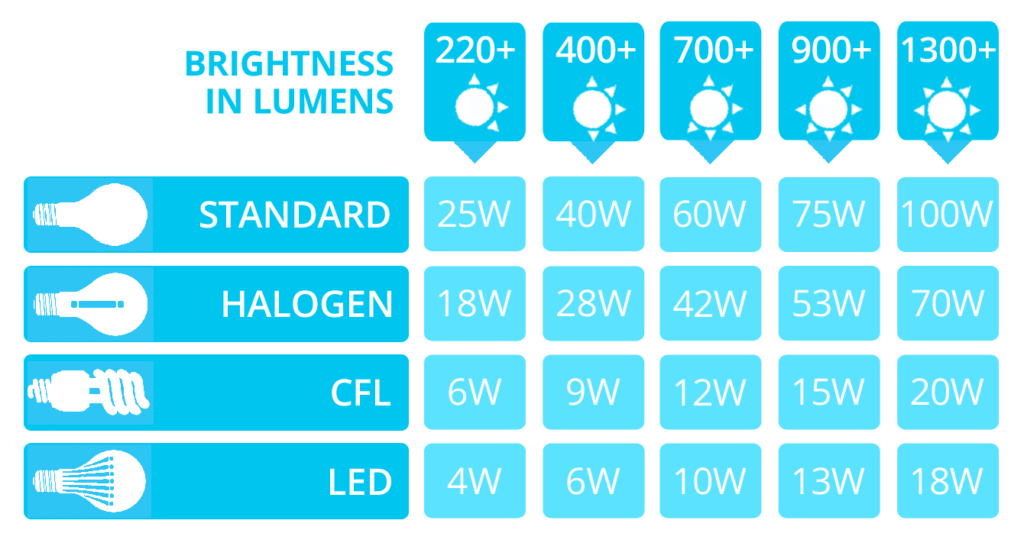

If you’re switching from incandescent to LED bulbs, you’re likely going to notice that the measurements don’t line up. For example: your incandescent bulb probably has a big 60W at the top, and the LEDs you’re looking at are advertising in lumens.

Lumens and watts measure different things.

- Watts (W) measure energy use

- Lumens (lm) measure brightness

In the past, because there was only one type of light bulb, the incandescent, energy use in watts was directly related to how bright the light was. A 100W bulb was brighter than a 60W bulb, a 150W brighter than a 100W, and so on. With the rise of new lighting technologies, this relationship broke down.

Now you need to look at the brightness of the LED bulb—not the wattage—to compare it to your existing lights. Brightness is measured in lumens (lm), which is found by measuring how much light something creates in a given amount of time. Now, lumens is what you need to look for when looking at light bulbs.

Light bulbs with identical lumen values are identical in brightness—this is important. Whether it’s a 60W incandescent, 14W LED, or a 10W LED, if they have the same lumens value, they have the same brightness. The differences in wattage just mean they differ in cost to use, with the higher wattage costing you more for the same amount of light.

What does “60 watt equivalent LED” mean?

A lot of LED bulbs are marketed as “60 watt equivalent,” but if it’s not actually 60W, what does that mean? In simple terms, it means that this bulb can be a 1 to 1 replacement for what was the most common type of light bulb: the 60W incandescent bulb. But there are some details worth going over here.

A couple decades ago, a bunch of lighting and electricity nerds at federal agencies with acronyms like NREL, DOE, and EPA decided that the average 60W incandescent bulb is equivalent to 800lm. In practice, you can expect a 10% difference from the average, meaning 60W incandescent bulbs could have a brightness of anywhere from from 720lm to 880lm.

Because this value is an average and not a standard, manufacturers are free to market with it and use it however they want. Meaning a LED bulb with 750lm, while below the average for a 60W incandescent, has a brightness within the reasonable expected value for an individual 60W bulb and might call itself a “60w equivalent.”

In general, you can use 800lm as the brightness of the 60W incandescent bulb you need to replace. But if you see a bulb slightly over or under 800lm, don’t treat them the same. If a bulb has fewer lumens than the alternatives also marketed using “60W equivalent,” be sure to take that into account when looking at the price.

Here’s a watts vs. lumens chart courtesy of the Light Bulb Company that might be helpful in switching bulbs.

How much do LED lights save per year?

The average home with incandescent bulbs uses about 2,000 kWh of electricity per year. And that results in almost one ton of carbon being released into the atmosphere—just for lighting. For reference, that’s the same amount of emissions as a flight from NY to Europe.

At the national average of $0.10 per kWh, that means these homeowners spend about $215 per year on lighting. By switching to LEDs, the average homeowner can bring that number down to $50–$115 and cut roughly 600 pounds of carbon per year, depending on where they live.

Of course the actual amount of electricity your home uses on lighting will depend on a number of factors including:

- How many light bulbs your home has

- How much you use your lights

- What kind of bulbs you currently have

We won’t get super deep into the math here, but if you’re interested in getting into the nitty gritty, take a look at our LED savings guide to figure out precisely how much you can save.

How many lumens do I need?

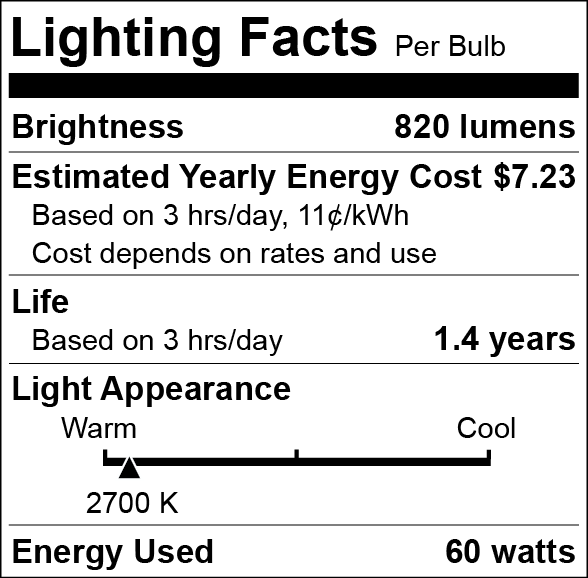

When you’re buying new bulbs you’ll probably see a label like the one below with things like lumens, yearly energy cost, lifespan, and light appearance (or color).

Let’s go over what all this means.

LED Lumens

The brightness of the bulb you need depends on personal preference and where you intend to place the bulb. Lumens per square foot (lm/sqft) is a measure of how much light you need in an area.

Generally, the more detailed work you expect to do in an area, the brighter you want the space to be and the higher lumen per square foot value you want. Makes sense.

Remember: lumens are the only way you can compare the brightness of bulbs, and they mean the same thing no matter what the other statistics of the bulb are.

LED energy cost per year

LEDs save money and energy. The label will show you the estimated energy cost per year per bulb, which means you don’t need to do any math. Add up this value for all the bulbs you buy, and you’ll get a great estimate on your total yearly costs.

But keep in mind this is just an average based on 3 hours of use and $.11 per kWh electricity costs. If you keep your lights on all day or if you live in a place like Massachusetts where electricity is twice the national average, you should expect to pay more.

LED lifespan

On every LED bulb label, you’ll see a box for “Life,” which gives you either the total hour lifespan or the total year lifespan (given a specific amount of daily use). The expected LED lifespan should be about 25,000 hours, so if it’s drastically lower, you might want to try something else.

Note: if it gives you the lifespan in days, just multiply that number by 365 and then by the number of daily use hours it gives. (In the label above, 18.3 year * 365 days * 3 hrs/day = 20,038.5 hours.)

LED light appearance

Light appearance — also called correlated color temperature (CCT) or just temperature — is the “color” the light is, meaning what sort of light the bulb gives off. This is measured in kelvins (K). And it’s one of the most noticeable differences between light bulbs (if you’ve ever bought a really cold, blue light bulb for your bedroom you know what we mean).

The cooler the light, the closer to daylight the human brain thinks it is. This makes higher temperature lights perfect for areas where you need to be alert and be able to perceive contrasts, like a kitchen. But these kinds of lights would make it harder to fall asleep if used for reading in bed. Generally, you should use warmer colors (below 3500K) for 70% of your lighting, saving the whiter or bluer lights for areas where more detailed work is done. (Or if you’re like the author of this guide, you’ll just want to stick with warm lights for your entire home!)

To find out which color bulb you need for each room, take a look at our guide to LED colors and temperatures.

LED energy use in watts

The final box gives energy use in watts. The lower the watts, the cheaper the bulb is to use. Again, consider that the typical incandescent bulb uses 60W, the typical CFL uses 16W and the typical LED uses 10W.

Other things to consider before buying LED bulbs

It will cost between $1 and $5 a bulb to replace your existing bulb with a LED.

Why the big range? All the stats above will factor in, but it’s also dependent on the quantity purchased, the type of bulb purchased, and where you purchase the bulb.

Quantity of bulbs

Bulk purchases of any type of bulb will naturally make it cheaper to switch over. But always make sure to check the label.

For example, this deal of 24 bulbs for $24 seems great, with a price per bulb of $1, but the bulbs have a far lower lifespan than you’d expect from LED bulbs (15,000 hours vs. the expected 25,000 hours). They’re also less bright than alternatives also marketed as “60 watt equivalent” (750lm vs. the expected 800lm). While this is still a better light than an incandescent or CFL alternative, it might not be the best deal in the end.

Energy compliance

Always check to see if the bulk order of bulbs is Energy Star compliant and can be sold in California. Energy Star is a mark of quality that ensures that the bulb you’re getting follows a set of strict quality and lifespan guidelines. The California Energy Commission sets the strictest efficiency requirements in the country, and if an LED bulb is unable to be sold in California, it may be less efficient or otherwise inferior to other alternatives.

Type of bulb

How complicated you want your bulb to be is up to you. You can get a simple LED bulb, one capable of being used in a dimmer switch, or even a “smart bulb,” which can emit different colors of light and be controlled by your phone or other smart devices.

The more complicated the bulb, the more expensive it will be, but this gives you the ability to customize your home’s lighting. Generally, you can expect a standard bulb to run between $1 and $5, a dimmer bulb between $2 and $7, and a smart bulb between $10 and $40.

Can I get an LED light bulb rebate?

Local utility and state programs can help you lower the cost of switching to LEDs even more. Your local power utility has as much of an incentive to cut your home electricity use as you do. Yes, it means they’re able to sell you less electricity, but to the provider, it’s worth more today to avoid the potential costs of producing more electricity. Energy efficiency allows the utility to continue to run the power grid with the existing power plants and lines even with population growth, and not have to make costly investments in new power plants or power lines that may not pay for themselves for decades.

In part because of this, all utilities run some sort of residential energy efficiency program to help offset some of the costs of retrofitting or upgrading your home.

Many of these programs come in the form of rebates, where you send the utility a proof of your purchase and they send you a check for some portion of the cost. You can use this link to see if your local utility is running a rebate program for LEDs.

Because of the success of the programs, many of them have been successfully completed, terminated, or no longer include LEDs. If your local utility doesn’t have a rebate program, it most likely has what is called “upstream incentives.” Your local utility will work with (and often just give money to) manufacturers and local retailers in order to guarantee lower prices at the store. This often results in the same price savings as a rebate, but with less paperwork for you.

Which LED bulbs should I buy?

Using all these factors, we did research for our own home and office to find what might be the best bulbs. Our local utility no longer had any efficiency programs aimed at LEDs, so we looked online for the best deal.

We found this bulk order of 6 bulbs for $15.99, or $2.67 per bulb. It’s a perfect replacement for most of the average home’s lights, with the statistics we expect from a modern LED bulb. They are 800lm, as bright as most of the incandescents or CFLs we already have. They’re capable of being used in dimmer switches, so we don’t have to go out and purchase a second set of bulbs for those rooms. And they have a lifespan of 25,000 hours, so we won’t have to think about replacing the bulb for decades.

Of course, you might have different requirements: maybe you don’t have any rooms with dimmer switches (and don’t plan to). Or maybe you’re looking for bulbs just for your bedroom and want them to be dimmer because you use them right before bed. Keep in mind your personal preferences when making that decision.

Read more about LEDs and home energy efficiency improvement projects

- LED savings guide

- LED temperature and color guide

- How to save money and energy with a heat pump

- Everything you need to know before switching to a heat pump

- Heat pump water heater buyer’s guide

The post LED Lighting Buyer’s Guide appeared first on Carbon Switch.

]]>